This blog entry describes what my students and I did during Week 2 of the Emerging Tech (NSF Grant) project. The events in this blog entry took place at the same time as the events in this article. As a pair, these describe what a PBL teacher does while running two projects in two different preps at one time. To see accounts on earlier or later weeks of these projects, go here.

Week 2, Day 1 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

During Day 1, I was not available to work directly with the students because I was at a training related to my responsibilities as Campus Testing Coordinator. The students started work on informal presentations on physicists who had contributed to our understanding of nuclear phenomena and quantum mechanics. The students delivered these presentations on Day 4 of this week.

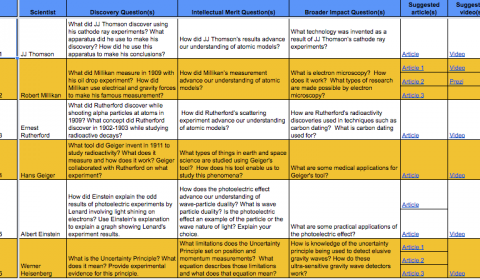

Each team was assigned a different physicist. To start preparing students for a grant they would write several weeks later, the research questions for each physicist focused on the research of the physicist, its intellectual merit, and its broad impact. The assigned physicists and related questions for teams 1 to 6 are shown in this linked image. I provided them with at least 3 age-appropriate and accurate sources to research the questions to streamline their research process.

Each team was assigned a different physicist. To start preparing students for a grant they would write several weeks later, the research questions for each physicist focused on the research of the physicist, its intellectual merit, and its broad impact. The assigned physicists and related questions for teams 1 to 6 are shown in this linked image. I provided them with at least 3 age-appropriate and accurate sources to research the questions to streamline their research process.

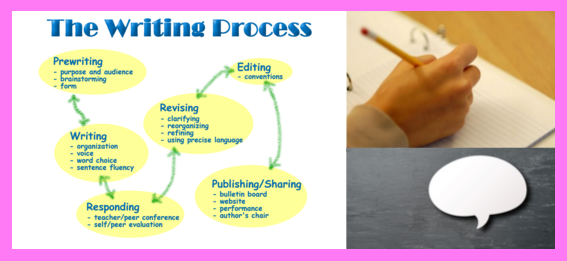

Each team was also given a template slide deck that limited teams to 3 slides per scientist (see linked template). The template also constrained students to mostly images and very limited text on the slides. The bulk of their responses to the research questions were hidden in the slides’ speaker notes sections.

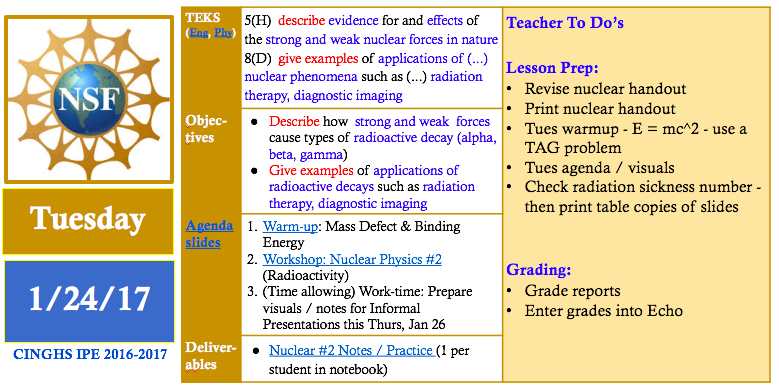

Later on Day 1, I finalized a lesson for Day 2 of this week by analyzing test bank questions related to TEKS on nuclear phenomena and the weak nuclear force. I found that my workshop needed to focus on types of radiation (alpha, beta, and gamma) and their relationships to nuclear forces (weak and strong) and various technology. They also needed to introduce half-life and how to use half-life to select appropriate isotopes for different types of technology. I designed a graphic organizer that included an embedded half-life chart and questions that asked students to interpret the chart to select isotopes for different technology applications – see Day 2 handout.

Week 2, Day 2 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

Early on Day 2, I made some minor adjustments to my visuals for the upcoming Nuclear Workshop because I needed to look up specific radioactivity values that corresponded to harmless and harmful levels of radiation and their effects. I typically outline and draft lesson plans and related resources several days ahead of time and then refine them until the day before (or day of) the actual lesson.

Later on Day 2, I facilitated a workshop on Radioactivity with the IPE classes. In this workshop, we introduced healthy and dangerous levels of radioactivity and used these thresholds to interpret the harmfulness (or harmlessness) of different types of radioactive technology. We introduced the idea of half life and used specific half lives to discuss whether or not various isotopes were safe (or not) for consumer use. We also introduced 3 types of radioactive processes (alpha, gamma, and beta) and discussed their connections to nuclear forces and technology applications. After the workshop, students had time to answer the questions on the graphic organizer and to continue developing their presentations on nuclear / quantum physicists.

Later on Day 2, I facilitated a workshop on Radioactivity with the IPE classes. In this workshop, we introduced healthy and dangerous levels of radioactivity and used these thresholds to interpret the harmfulness (or harmlessness) of different types of radioactive technology. We introduced the idea of half life and used specific half lives to discuss whether or not various isotopes were safe (or not) for consumer use. We also introduced 3 types of radioactive processes (alpha, gamma, and beta) and discussed their connections to nuclear forces and technology applications. After the workshop, students had time to answer the questions on the graphic organizer and to continue developing their presentations on nuclear / quantum physicists.

Later on Day 2, I finished grading revised reports from the previous IPE project on Rube Goldberg machines. In this project, students built and tested Rube Goldberg devices in order to investigate conservation of energy and conservation of momentum.

Week 2, Day 3 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

Day 3 was the final work day that students had to prepare for their informal presentations on nuclear / quantum physicists. In the warmup, we practiced using the half life chart to select the appropriate isotopes for specific technology applications. During the warmup discussion, I was able to repeat and model correct thinking relating to interpreting the half lives of isotopes in the context of emerging technology.

While the students worked on their slides, I started contacting potential panelists in order to provide feedback to students during Week 5 of the project when students would draft their grant proposals. I drafted a recruitment letter that summarized the project logistics and the types of support the student needed. I linked the recruitment letter to a Google form that gathered information on volunteer panelists’ degrees, areas of expertise, and availability. By the end of this week, this work yielded 5 panelists, a great number to support 10 student teams. If you’d like to volunteer to be a panelists at CINGHS, click the linked form above.

While the students worked on their slides, I started contacting potential panelists in order to provide feedback to students during Week 5 of the project when students would draft their grant proposals. I drafted a recruitment letter that summarized the project logistics and the types of support the student needed. I linked the recruitment letter to a Google form that gathered information on volunteer panelists’ degrees, areas of expertise, and availability. By the end of this week, this work yielded 5 panelists, a great number to support 10 student teams. If you’d like to volunteer to be a panelists at CINGHS, click the linked form above.

Also during student work time, I ordered equipment from the UTeach department that related to an upcoming emission spectra lab. I thought this equipment was critical to give students hands on experiences related to modern physics and to give students a break from a project featuring lots of online research and very few hands-on research activities.

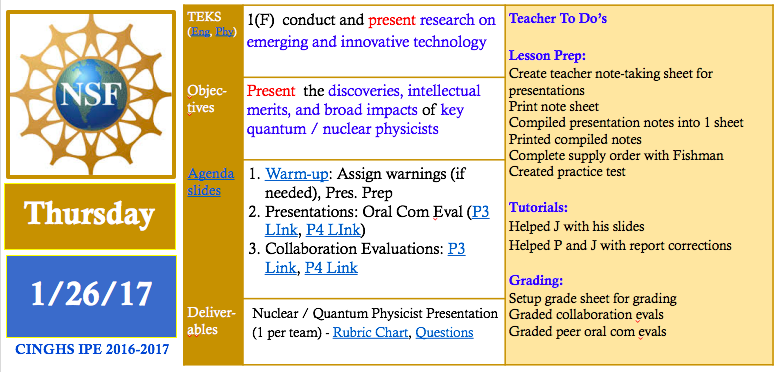

My co-teacher and I prepared for presentations the following day by setting up Google Forms to gather peer grades on collaboration and oral communication. I created a set of note sheets for capturing our teacher notes on teams’ presentations on quantum and nuclear physicists. To prepare for our notebook grading day later that week (Friday, Day 5), we decided what assignments we would grade for that week and how many points we would assign to each assignment in each of our class’s learning outcomes (Oral Communication, Written Communication, Collaboration, Agency, Knowledge & Thinking, Engineering Content, Physics Content).

Week 2, Day 4 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

Early on Day 4, I decided to create an experimental tool to keep students in the audience of presentations more engaged. I created a graphic organizer that students could use to take notes on other teams’ presentations. I showed this tool to my co-teacher, Mr. Fishman, and shared a related idea: why not let presenting students’ stamp the parts of the graphic organizer related to their presentation so they could get real time feedback on how well they communicated their key points and also hold their peers accountable for taking good notes? He was willing to try it.

The experiment was a success. The students seemed to really enjoy stamping their peers. Also several students insisted on making their peers improve their notes prior to stamping their papers so the level of accountability was kept high throughout the note-taking activity. In addition to note-taking, students in the audience evaluated the presenters on their oral communication skills. Meanwhile, my co-teacher and I took notes on their presentations relating to the rubric so we could use our notes to supplement what we would later gather from reviewing their slides and their hidden speaker notes. Sometimes students say more than they write, so we use both our notes from what they say and what they write to evaluate their presentations and related research.

Later on Day 4, I used pivot tables to analyze data gathered via Google Form to generate peer grades relating to collaboration and oral communication. I typed out my presentation notes in order to create a graphic organizer that summarized the key points delivered by all teams in both class periods. I shared these notes with students the following day so they could learn from students in both periods. See linked notes on tne left. At the end of Week 4, the students used these notes and other notes to take an open notebook test on nuclear physics, quantum mechanics and biotechnology.

Later on Day 4, I used pivot tables to analyze data gathered via Google Form to generate peer grades relating to collaboration and oral communication. I typed out my presentation notes in order to create a graphic organizer that summarized the key points delivered by all teams in both class periods. I shared these notes with students the following day so they could learn from students in both periods. See linked notes on tne left. At the end of Week 4, the students used these notes and other notes to take an open notebook test on nuclear physics, quantum mechanics and biotechnology.

Week 2, Day 5 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

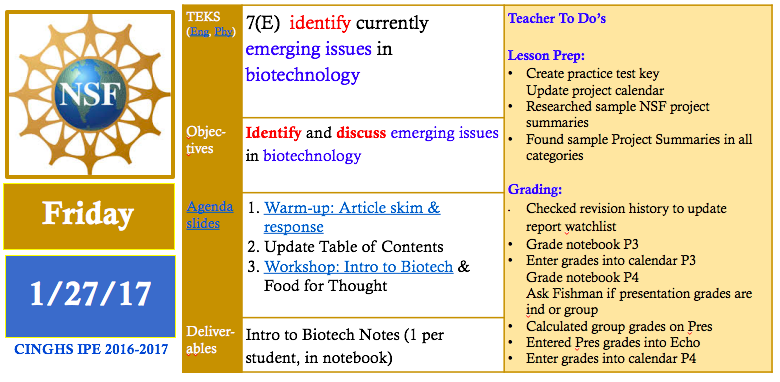

On Day 5, we switched gears by introducing emerging (and ancient) examples of biotechnology. We opened the class with a discussion on a Washington post article on the creation of pig-human embryonic chimeras. After this introduction, Mr. Fishman led the class through an introductory workshop / discussion on biotechnology. Students were so open with their opinions and prior knowledge of biotechnology that the 1-day workshop spilled over into the following day.

Week 2, Day 6-7 IPE Emerging Tech (NSF Project):

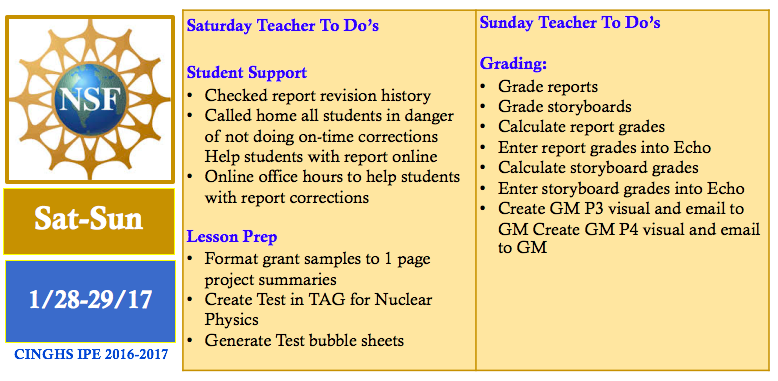

On Saturday morning, I checked the file revision histories of report documents to check which students were in danger of not meeting the final report revisions deadline. I called the homes of all students who needed extra reminders and parental support to meet this important deadline. Later on the day, I held online office hours to support students working on their report corrections. While doing this, I gathered and re-formatted sample grant summaries that students would eventually analyze to learn the style of writing related to their grant proposals. I also created a test on Nuclear Physics and generated the question sheet and bubble sheets for this test.

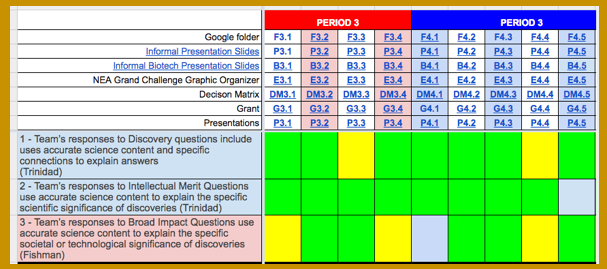

On Sunday, I graded the final revised versions of the students’ engineering report from the prior project (the Rube Goldberg project). I also graded students’ presentations from earlier in the week using my presentation notes and also considering all the written texts and images on students’ slides and their speaker notes. Using our IPE tool, the rubric chart (see linked Google Sheet), I was able to grade their presentations fairly quickly and enjoy the rest of my weekend. The presentations were easy to grade because most of the students had done the assignment perfectly or nearly so. I think the pre-selected articles, the specific research questions and the verbal feedback on the slides given throughout the week had really helped the students create quality products.

enjoy the rest of my weekend. The presentations were easy to grade because most of the students had done the assignment perfectly or nearly so. I think the pre-selected articles, the specific research questions and the verbal feedback on the slides given throughout the week had really helped the students create quality products.

For more grading tricks, go here. To continue reading about this project, go here.