From June 9 to June 19, 2016, six trainers from Advanced Reasoning in Education (ARIE) embarked on our first Project Based Learning (PBL) training tour of China. Stephanie Ehler, Sarah DiMaria, Stuart Ray, Steven Zipkes, Stephanie Ehler and I facilitated three 3-day trainings in Hohhot, Beijing, and Shenzhen. During our workshops, we all enjoyed working with many passionate, creative and hard working teachers, translators, professors, and administrators in China. We hope that this PBL tour will be the first of many opportunities to collaborate with educators striving to implement PBL in China.

On Thursday, June 9, our team flew from Austin to Chicago to Beijing, China. We arrived in Beijing on Friday, June 10. Our host professor from the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Dr. Guoli Liang, and a team of teachers and translators en route to a PBL Conference in Hohhot welcomed us at the Beijing airport. We all gathered for one big group picture before splitting our full ARIE team into two smaller PBL training teams. Stephanie Ehler, Stuart Ray and Sarah DiMaria left Beijing to facilitate a 3-day training in Hohhot. Steven Zipkes, Stephanie Hart, and I remained in Beijing to lead a 3-day training at the Zhongguancun No. 3 Primary School. On our first evening in Beijing, Professor Liang took Steven, Stephanie, and I to a traditional noodle shop that prepared fresh noodles from scratch. The noodle dishes were delicious! What a great first meal in China!

On Saturday morning, June 11, Steven, Stephanie and I visited the Zhongguancun No. 3 Primary School. We were taken on a wonderful school tour of this unique campus and we met with our translators Professor Xiang and Professor Zhu to prepare for Day 1 of our PBL training the following day. The Zhongguancun No. 3 Primary School was one of the most amazing and beautiful schools I have ever visited. The school had so many features that promoted positive culture and innovative teaching / learning styles. The fitness facilities included an indoor pool, an indoor and an outdoor track, a stadium with rock climbing wall and 2 full size basketball courts, and several dance / yoga studios. The school itself was divided into six sub-schools that were branded by the six colors of the rainbows. The school within a school design created learning community spaces that had the intimacy and closeness of smaller schools. Within each school, the classrooms were arranged in pods that were designed to promote collaboration among classes. These pods included large common work areas and 3 to 4 classrooms separated by dividers that could be opened to integrate classes that housed different grade levels. In addition to these classrooms, there were many specialty classrooms that promoted different types of learning: tea rooms, etiquette rooms, science labs, art studios, wood / metal workshops, libraries, computer labs, etc. The staff work rooms were very inviting and had modular furniture that supported collaborations of educator groups of varied sizes. The beautiful Hall of Achievement auditorium that housed our PBL training had tables, seating, lighting, and large project screens that made the room look like the site of a TED Talks conference. Gardens flourished in many classrooms and throughout the school grounds. Overall the school was really beautifully and deliberately designed; it felt like every detail, large and small, served to create a positive innovative learning space for students and educators. (For more school tour pics, go here.)

On the afternoon and evening of Saturday, June 11, two college students volunteered to take Stephanie and I to the Forbidden City. We arrived in time to tour the grounds for a couple hours. The Forbidden City was so vast that we only got to walk through a small section of the grounds. It was so amazing to walk through a place that was filled with so much beauty and that was steeped in so much culture. I felt very humbled while appreciating structures that were several hundred years older than the USA. After the Forbidden City closed, our tour guides took us to gardens and pavilions located on a large hill at the very center of Beijing. From the top of this hill we were able to see amazing views of the Forbidden City and many parts of Beijing. From these great heights, we were able to notice and appreciate the symmetry of the buildings in the Forbidden City. On our way back to the hotel, we got to experience public transportation in Beijing by taking two buses. The busses were very cheap (2 RMB ~ 30 US cents) and fun to ride. On one of the busses, a family asked Stephanie if their shy son could practice his English with her and she spent some time chatting with him. She talked with him with the same patience and enthusiasm that many of our Chinese hosts extended to us while we attempted to speak a few Chinese phrases. Throughout our stay here, I really enjoyed the Chinese people’s reactions to my attempts to speak Chinese. Many people gave me a lot of positive encouragement and helpful tips that helped me learn more Chinese words and phrases. (For more Forbidden City pictures, go here.)

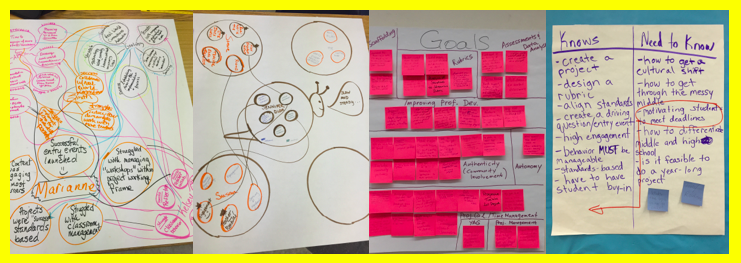

On Sunday, June 12, Steven, Stephanie, and I kicked off the PBL Training in Beijing with approximately 100 participants. I started off the training with our project launch. From the start our participants worked very diligently while taking notes and compiling their Knows and Need-to-Knows. Stephanie led the Project Ideation session. We had to work very hard with the participants to help them understand how to choose national standards and how to use these to start brainstorming project products and driving questions. Over the course of the conference we began to understand the differences in the ways the USA and China communicate their curriculum expectations through standards and ancillary materials. In the USA, we have very detailed standards that give the specific topics and skills that students need to learn at each grade level and content. In China, the national standards are very abstract and broad and are supplemented by more detailed curriculum goals that are contained in nationally prescribed textbooks. Once we were able to understand the differences in our systems, we were to communicate with the Chinese teachers in ways that helped them to select specific curriculum goals grounded in national standards and use these as springboards for project ideas.

We celebrated a successful Day 1 of training by eating at a Hot Pot restaurant. We enjoyed the excellent food, service, and company at our dinner. The food was spicy enough to numb our mouths in a way that surprisingly tasty and pleasant. A performer did a dance during our dinner that involved fan flourishes and some cool, quick mask changes. We shared this beautiful fun meal with teachers from Finland, Professor Liang, some translators, and Laura, a professor from Stanford University.

On Monday, June 13, Day 2 of the PBL training, Stephanie and I facilitated workshops on Rubrics, Scaffolding and Assessments. We were joined with a new translator, Liting who had attended an ARIE PBL training in Manor Texas in 2014. She was also Kevin Gant’s translator during a PBL training he led in Chongqing and Beijing in 2014. It was so great to have a translator with several PBL experiences join our team. She was able to help us add more depth to our presentations that built on the knowledge we shared the day before. She was also very good at project management. She was great at keeping work sessions on time and letting us know when participants needed more or less time to complete tasks. On Day 2, we presented workshops and facilitated work sessions that enabled the participants to draft a project rubric and a scaffolding and assessment plan for their projects. Many teams drafted their rubrics and scaffolding / assessment plans in their conference booklets AND on chart paper. Twice during the day, we gave the participants opportunities to give each other peer feedback on the project elements. On the first peer feedback session, they presented their rubric drafts and received feedback that related to a checklist of good rubric characteristics. On the second feedback session, they presented their driving questions, products, scaffolding and assessment plans and got feedback on the alignment and authenticity of their projects. During each of the feedback sessions, the participants were very engaged while they presented and gave feedback. They started to give each other many good ideas that helped them refine their early drafts of their projects.

We closed Day 2 by revisiting the PBL training rubric and giving the participants time to work on their Day 3 presentations based on the rubric expectations. We gave the teams opportunities to choose their presentation format (Powerpoint or Chart Paper) and to sign up for Critical Friends sessions. We were surprised that the teams nearly evenly split up into 6 teams who preferred to present by chart paper and 6 using Powerpoint. The teachers worked diligently on their rubrics and also helped up prepare for Day 3 by updating their Know and Need-to-Know charts. They circled their resolved Need-to-Knows and added an arrow pointing to the Know column. They also added new Need-to-Knows based on the PBL Training rubric. We collected these charts and our translators translated the unresolved Need-to-Knows in order to help us frame our workshops for Day 3. (For more Day 2 training pictures, go here.)

During the evenings of Day 2 and 3 of the PBL trainings, Stephane and I lingered near the school while waiting for Steven who was presenting the PBL Leadership Track of the training to administrators in the evening. During his 2 hour sessions, Stephanie and I spent most of our time resting in a nearly coffeeshop called Naan’s Coffeeshop. It was a really beautiful space that was decorated with mismatched chairs, chandeliers, indoor living trees, and many bookcases. The most beautiful bookcases extended from the floor of the lower level of the shop and extended to the ceiling of the second floor of the shop. We enjoyed their specialty toasts. They were similar to large slices of Texas toast seasoned with cinnamon, caramel, and fresh whipped cream. We also enjoyed their coffee in several forms (expresso, lattes, etc). Each morning we stopped at Naan’s for several coffees to go (or “takeaway” as they call it in China). In the evening while we were waiting for Steve to finish his leadership training, Stephanie and I took our time and used the space and its drinks and treats to relax and mentally recharge after our long days of PBL training. The bears posing with us in the pictures below were used to label tables so waiters could give customers their correct orders. On our first day at Naan’s we did not understand what the bears were for so we kept trying to return our bear. We thought they were trying to sell us souvenirs we didn’t want. We felt pretty sheepish when we finally realized why the waiters were so insistent that we hold on to our bear.

After these recharge sessions, it was easier for us to resume our preparations for the upcoming days of training which usually occupied us till it was nearly time for bed. During our preparation sessions, we practiced explaining our visuals in ways that captured the essential ideas in the slides in ways that were as clear and concise as possible in order to help out our translators. We also made minor adjustments to the sessions to include participant deliverables that gave participants opportunities to make their thinking visible and to practice applying the content in the session. For example on Day 2, we included a Scaffolding Assessment graphic organizer that had participants plan scaffolding activities and their associated formative and summative assessments on chart paper. Creating this visual helped our participants brainstorm and display instructional ideas that started bringing their projects to life. I was able to connect their ideas to project calendars while presenting the Project Management workshops on Day 3.

On Tuesday, June 14, Stephanie and I led the final workshops of our three-day training. In the morning, Stephanie led a workshop on Entry Events and then gave participants time to brainstorm entry event ideas. For the remainder of the morning, Steve, Stephanie and I co-faciilitated sessions on Project Management. We led mini-workshops that offered tips on how teachers and students can better manage projects by managing time, student work, and people. We tried our best to connect our presentations to the unresolved Need-to-Knows from the previous days. We closed the morning by having one team present their project and facilitating a model Critical Friends session in order to show participants what they had to look forward to after lunch.

During the afternoon, the remaining teams presented and received Critical Friends feedback. The teams who presented on Power Point added a Critical Friends slide and translators uses this slide to type out their Critical Friends feedback. The teams who presented using chart paper had their Critical Friends feedback written on large white boards. After the sessions, the teams took pictures of their Critical Friends feedback (I Likes, I Wonders, and Next Steps) before the boards were reset for the next Critical Friends session. The feedback that the participants gave each other was very detailed and practical. Many of the tips could be used to improve their projects. The project themselves were very creative, engaging, and complete. Many teams were able to present fairly complete rubric drafts, entry event ideas and scaffolding and assessment plans. We were very impressed by the amount and quality of the work the participants produced during our 3 day PBL training. At the end of our training, we took many groups pictures including the group picture featuring our translator team shown below. We exchanged some heartfelt and sad goodbyes with our translator team because we had grown close over the course of working closely together over the 3 days. (For more Day 3 Training pictures, go here.)

On Wednesday, June 15, Stephanie Hart and I were not scheduled for any trainings or meetings. Instead we followed Professor Liang’s suggestions and ventured by ourselves to the Summer Palace. We showed our taxi driver an iMap screenshot of the Summer Palace location and we were off! We were surprised by the size and beauty of the Summer Palace. The grounds included many palace complexes that surrounded a small lake. During our explorations of the place, we visited all the grounds that surrounded the lake. It took us six hours to finish walking through and viewing the sites that surrounded the lake. We explored beautiful temples, museums, gardens, palaces, and performance spaces. We climbed many old and beautiful bridges and stairs to reach our sites. We finished our tour by eating at a restaurant in an open market alongside the lake. The water views were very peaceful and refreshing. The whole day we strolled around in a reverie taking pictures of one beautiful site after another; it was like walking through paradise. I felt like I had stepped into the most beautiful free exploring video game ever. After exploring the palace, we showed another taxi cab driver a screenshot of map site that was supposed to take us to a flea market area of Beijing. Two hours later, we landed in what looked like a garment district. We walked around for awhile and couldn’t find the flea market area so we gave up and used our hotel business card to direct another cab driver to take us back to our home base. By the end of the day, Stephanie and I had trekked 8.6 miles. (For more Summer Palace pictures, go here.)

On Thursday, June 16, Steven had has first morning without presentations or conference meetings. Professor Liang arranged for a driver to take Steven, Stephanie and I to the Great Wall of China. On the tour bus to the wall, a kind woman gave us freshly picked apricots and plums. We ate some on the bus and packed some for snacks during our trek on the wall. We took a chair lift to the top of the wall and then proceeded to climb up and down the many steps connecting the towers of the wall for three hours. The climbing was fun and very challenging. The towers gave us time to take breathers, enjoy refreshing breezes, and take astoundingly beautiful pictures. Again, I was very humbled by China’s very rich and old culture. I felt so small and insignificant compared to the vastness of the Wall’s history and physical size. While on the Wall, we learned the following valuable lesson: do NOT ever buy souvenirs near the wall grounds. These were overpriced. The souvenirs that were in the tourist area that was a tour bus ride away from the wall had more reasonable prices and the vendors were more willing to drastically cut and negotiate prices there due to the high competition among the many shopkeepers in this tourist area. Before heading back to Beijing, Steve, Stephanie and I enjoyed a very delicious lunch with tasty dumplings, pork ribs, and Peking duck. (For more Great Wall pictures, go here.)

Thursday evening, we traveled with Professor Liang and several teachers and administrators to Shenzhen. Our plane was delayed so we left the airport around 11:30 pm and arrived in Shenzhen around 2:30 am Friday morning. We arrived at our hotel close to 5 am. It is a good thing I can fall asleep nearly anywhere. I slept on the plane and the bus to the hotel. I was able to combine these naps with another 1.5 hours nap in the hotel before it was time to wake up and help with the final day of PBL training in Shenzhen. The previous two days of training had been facilitated by the other members of our ARIE team, Stephanie E., Sarah, and Stuart.

On Friday, June 17, our full ARIE team reunited at the No. 4 Yucai Primary School and co-facilitated the final day of PBL training in Shenzhen. It was so great to see Stephanie E., Sarah, and Stuart again. No. 4 Yucai Primary School was another beautiful school. We presented our workshop in their spacious library. During workshop breaks, we toured the school and several classes asked us to come inside and take pictures with the students. The students were so happy to take pictures with us and to practice talking English with us. They were very excited to have us visit their campus. Just as in Beijing, I was impressed by the enthusiasm and work ethic displayed by the participants as they wrapped up their projects and participated in the Day 3 workshops and activities. They asked MANY good questions. I could sense that they were trying to learn as much as possible in order to be successful in their first attempts at PBL.

Due to the number of participants and technology constraints, we conducted Critical Friends in gallery style. Each team presented twice and received written feedback using the Critical Friends sentence stems (I Likes, I Wonders, Next Steps). A translator, Evelyn, followed me during my gallery walk and helped me to understand the presentations so I could give feedback. They were very enthusiastic about my feedback. Some of them kept taking pictures while I wrote out my I likes, I wonders and Next steps. They did this even while I reassured them that I was going to give them the post-it notes that held my feedback. To celebrate the end of a successful session, we did the Cuban shuffle with all the participants and took many large group pictures. The participants were very coordinated. We were able to fit a surprising number of dancing participants in a small space due to their great dance coordination and cooperation. (For more Shenzhen pictures, go here.)

On the evening of Friday, Jun 17, we gathered the entire ARIE team, teachers and administrators from Shenzhen, and teachers from Finland for a celebratory dinner. We ate at a very good Japanese restaurant. We ate many courses of meats cooked hibachi style. The froi gras with caviar was amazing! After dinner, we watched a beautiful fountain show set to inspiring music. We also picked up desserts and coffees at a Costas Coffee shop. Stephanie Hart and I ate these in Steven’s room while helping him prepare for his keynote speech on the following day.

On Saturday, June 18, we had a whole day to rest and regroup. The entire ARIE team ate lunch together at a very good craft burger restaurant. I spent much of the day working in Stephanie Ehler’s room on an Assessment training for the Advanced track of the Think Global PBL Academy. Stephanie played very soothing music in her room that really helped keep me in the zone. Despite a spotty internet connection, I was able to get the session 95% complete on this day – a huge relief since I will present this session for the first time on June 21 at a PBL training in Clearwater, Florida.

In the evening, we attended the closing ceremony for the Shenzhen PBL Conference. We listened to very kind speeches that expressed a lot of gratitude for the PBL workshops from teachers and administrators. The principal of the school emphasized the importance of using instructional strategies that went beyond the textbooks. After the closing ceremonies, we had another celebratory dinner. This time we ate at a very good Chinese restaurant. We gave many toasts to celebrate the success of the training. Then we also started celebrating my birthday on June 19 a couple hours early. Our Chinese hosts gave many birthday speeches and toasts. I felt showered with good luck and many good wishes for the future. What a magical way to celebrate my birthday! 🙂

Overall our trip to China was really amazing! Our 10 day trip felt like it lasted for months because it was densely packed with many great experiences. I now feel really inspired to learn how to speak more Chinese and to collaborate with many more teachers in China and throughout the globe in the future. The trip made me feel very hopeful for the future of education in America and in China – we have so many great things in common. I met many teachers who also love to teach and who also love to learn innovative instruction methods that better prepare students to positively impact their present and future worlds. I truly hope that ARIE can continue to build partnerships with educators in Chine that will provide many opportunities for us to collaborate with teachers on implementing PBL in more classrooms and schools.

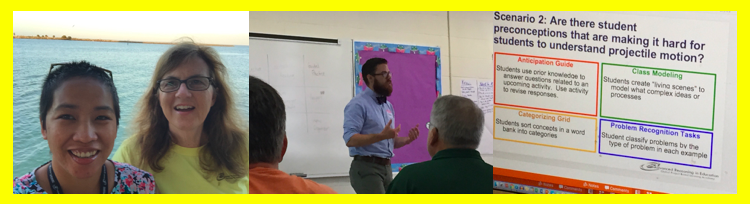

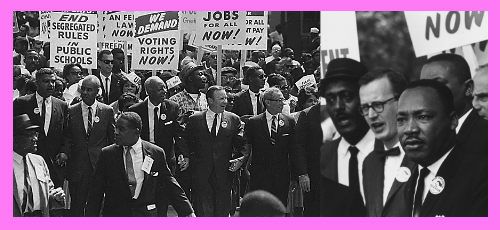

Structuring discussions to ensure active participation by ALL students can have numerous benefits for students. Students can learn how to explain and clarify their ideas, become aware of their assumptions, learn multiple perspectives, and connect new and prior knowledge. Teachers can encourage students who are used to having a passive role in learning activities to become active participants of discussions by implementing protocols that promote active participations for ALL.

Structuring discussions to ensure active participation by ALL students can have numerous benefits for students. Students can learn how to explain and clarify their ideas, become aware of their assumptions, learn multiple perspectives, and connect new and prior knowledge. Teachers can encourage students who are used to having a passive role in learning activities to become active participants of discussions by implementing protocols that promote active participations for ALL.

Chapter 7 from

Chapter 7 from